An exciting part of being a researcher of any level is the opportunity to travel to research conferences held all over the country and the world. However, the tricky part about a conference is that while the audience is typically knowledgeable about the general topic, there are so many contexts in which the specific topic can be covered. Do you work in animals? Cell culture? The immune system? The brain? I can wax poetic about intestinal structure and function, but ask me about the brain and I’m completely useless.

A research presentation usually includes a five-to-ten minute introduction to the organ or model system being used to interrogate the hypothesis. Often, this is composed of various animated cartoons to give the audience a visual aid. For me, a good introduction is always much appreciated, especially if I am unfamiliar with the system being used. If I haven’t followed the introduction well, the remaining presentation is lost on me. Lately, one of the trends I’ve been noticing is presentation of a video introduction in lieu of the cartoon option. I’ve found this approach is much more effective at making the subsequent research story easy to follow.

For example, I recently returned from a conference where a talk began with a beautiful video on how nerves form connections during development. I was left with what it might look like in real life for nerves to grow and innervate muscle—a visual learning experience that probably could not have been achieved with animated cartoons.

The second thing that stands out to me in this regard comes from clinicians who regularly perform procedures relevant to their area of research. At the same meeting, at least two investigators began their presentations with videos of clinical procedures. I was brought into the operating room for a corneal transplant and a bronchoscopy, all from the comfort of my seat. For me, this integration of the clinical experience with basic research gives me a great appreciation of how the results that follow are relevant to disease and potential therapies.

Conferences can be exhausting: eight hours of sitting in the same seat in the dark, furiously scribbling notes for your PI, counting down the minutes until the network reception (Food! Wine!), with breaks for coffee every so often (but not quite often enough). This new trend of video introductions certainly makes presentations more exciting, more memorable, and – most importantly – makes them more understandable to a potentially uninformed audience.

Have you noticed this trend too? Do you appreciate a video introduction?

Emily is a fifth year graduate student here to explore firsthand how technology and video can enhance your research experience. As scientists, we are on the cutting edge of new technologies that can take our work to the next level and allow us to find solutions to questions that were previously unanswerable. Let’s make use of the new and shape the future.

]]>

When we started BenchFly five years ago, in 2009, our mission was to make research a better career for current and future generations of scientists. Today we continue to work toward this goal using video as the primary means to educate scientists in companies, in universities and now in high schools! In the fall of 2013, we were incredibly fortunate to have met Kentucky teacher Tricia Shelton (thank you, Twitter!) arguably one of the most energetic, passionate, and dedicated teachers out there. In less than 12 months, our collaboration has resulted in a new video-based curriculum, called The ART of Video

When we started BenchFly five years ago, in 2009, our mission was to make research a better career for current and future generations of scientists. Today we continue to work toward this goal using video as the primary means to educate scientists in companies, in universities and now in high schools! In the fall of 2013, we were incredibly fortunate to have met Kentucky teacher Tricia Shelton (thank you, Twitter!) arguably one of the most energetic, passionate, and dedicated teachers out there. In less than 12 months, our collaboration has resulted in a new video-based curriculum, called The ART of Video , and a Gates Foundation grant supporting further assessment of the program’s potential in the classroom. Thanks to Tricia, we’re engaging with and developing those future scientists we’ve been thinking about since 2009.

, and a Gates Foundation grant supporting further assessment of the program’s potential in the classroom. Thanks to Tricia, we’re engaging with and developing those future scientists we’ve been thinking about since 2009.

But this is not about the ART of Video (this link will tell you more and show Tricia’s students in action). It’s about the human side–how the boundless energy of collaborators like Tricia and her students can fuel a project long before the funding arrives to support it. It’s about honoring the educators working day in and day out to create environments where future scientists can thrive. It’s about being grateful for organizations like The Gates Foundation who see a spark and are willing to fan the flames to see how brightly it can burn.

And finally, it’s about thanking the students and watching in amazement. At BenchFly, we never cease to be blown away by the quality of videos a high school student can produce with an iPad. Trust us when we say video is here to stay and the future of science looks bright.

As a new school year gets underway, we fire up the ART of Video with a fresh crop of students. Throughout the coming semester and year, we will track the progress of the Shelton class here on our blog and highlight some of the incredible video products they’re creating–so stay tuned.

To show your support for the Shelton Class, follow Tricia on Twitter and tell her thanks!

For more information about The Fund for Transforming Education in Kentucky, visit: https://www.thefundky.org/

]]> “Set timer for ten minutes.” Instead of the kitchen timers the rest of us use, the post-doc sitting behind me regularly uses Siri to time his experiments. As it turns out, it’s actually easier to tell a computer to set a timer for you than to do it yourself, and Siri is quickly becoming our lab’s newest research assistant. With a new iPhone model out each year, it’s not hard to believe that we’ll soon have everything we need on the little 2¼” x 4¾” device we can no longer go anywhere without. But what does that mean for us lab rats? And how can we leverage new technology to save us some time (something none of us ever have enough of)?

“Set timer for ten minutes.” Instead of the kitchen timers the rest of us use, the post-doc sitting behind me regularly uses Siri to time his experiments. As it turns out, it’s actually easier to tell a computer to set a timer for you than to do it yourself, and Siri is quickly becoming our lab’s newest research assistant. With a new iPhone model out each year, it’s not hard to believe that we’ll soon have everything we need on the little 2¼” x 4¾” device we can no longer go anywhere without. But what does that mean for us lab rats? And how can we leverage new technology to save us some time (something none of us ever have enough of)?

When I ditched my old Pantech keyboard phone for an iPhone 4 in 2010, I didn’t realize how much it would affect my lab life. Along with email, Google, Facebook, and HD cameras, smartphones also have the ability to put scientific tools at our fingertips.

In the five years I’ve been in graduate school, smartphones have become an everyday item — even not-so-tech-savvy PIs have the latest iPhone — and apps have evolved to the point where scientists now have their favorite tools all in one place. I can access and search journal articles using PubMed on Tap, view the latest edition of Cell on the Cell Press Journal Reader app, and count GFP-expressing cells using a tally counter app — all while streaming my favorite 90’s Pandora station.

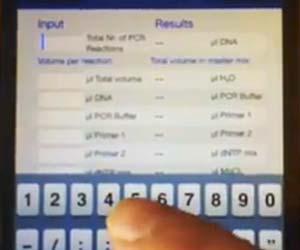

Although my computer is only a pipette’s throw away, I can usually find what I need using my iPhone with less work sitting at the bench in the middle of an experiment. Take Life Technologies’ Cloning Bench app as an example. Every calculator I would ever need is provided on a spinning wheel selector tool. With up to six different PCR reactions running at the same time, I can easily automate my workflow and save time. Similarly, I can design a restriction digest using New England Biolabs’ Restriction Enzyme Double Digest Finder without having to leave the bench. In the past, when I have a new student in the lab learning basic lab techniques, I typically referred them to Abcam’s website. Now, protocols for ELISA, IHC, and Western Blotting, among others, are all available with a couple touches on their app. In addition to experimental tools, there are also multiple apps with classroom potential for science-related learning. Exploring 3D animal and plant cells, signaling pathway overviews, and 3D protein structure modeling are just the beginning.

In addition to experimental tools as apps, we’re even turning smartphones into pieces of lab equipment. Want your own personal microscope? Done. Turning your iPhone into a microscope with up to 175X magnification is relatively simple according to this instructional video. We’ve incorporated this functionality in our lab for a measly $70: instead of spending hundreds of dollars on a new lens for our dissecting microscope, we bought a lens adaptor (ōlloclip®) that clips onto an iPhone lens, increasing the available magnification of the existing camera (and mobility) for a fraction of the cost.

While I firmly believe there is always the place for the traditional — I still prefer to read papers as hard copies — the milieu of smartphone tools available to facilitate the basics of experimentation is amazing. While the apps are often the same web tools that have long been available, they’re now conveniently located (literally) in your back pocket on one device you can take anywhere.

Although there is merit in decreasing smartphone use in favor of more personal interactions, overall I think the arguments for using smartphones to enhance your lab experience are good. Many of the tools I’ve mentioned still require basic knowledge of why and how the technique involved is used. Therefore, these shortcuts are not intellectual ones, but rather time-savers. Between working 11-hour days just to have experiments fail and trying to convince your PI that IpromiseI’mworkingeventhoughIdon’thaveanyfiguresyet, being a graduate student is hard enough. If being tethered to my iPhone in lab means finishing my experiment a half hour early because it took less time to set it up, I’ll take it.

So what’s next? Will smartphone technology eventually negate scientific products and the businesses that supply them? (Remember the Flip video camera?)

What smartphone tools do you use in lab? How have smartphones changed your lab experience? Head over to Google+ and let us know.

Emily is a fifth year graduate student here to explore firsthand how technology and video can enhance your research experience. As scientists, we are on the cutting edge of new technologies that can take our work to the next level and allow us to find solutions to questions that were previously unanswerable. Let’s make use of the new and shape the future.

]]>

While all that’s been going on, the BenchFly team has been…well, watching Tim Cook’s WWDC keynote, trying to avoid stories about politicians’ book tours, enjoying replays of Robin van Persie’s swan-dive goal, and sitting in slack-jawed amazement at Noah Hawley’s directorial brilliance. We’ve also been updating and expanding BenchFly, and we are really excited for the upcoming rollout of our new features and content. We’ve made tweaks to the site and put together short tutorial videos to help you get started using the platform. New features are also being added to the BenchFly video player, which we will be unveiling over the next several months. In addition, we are developing a series to take scientists at all levels through the logic and process of using video to improve work at the bench, collaboration, product training, and even sales and marketing. If you do science or work for a science company, BenchFly has you covered.

So, as the painfully overused saying goes, watch this space. The changes and new content will be appearing over the next few weeks. You may not care about Germany’s impending World Cup triumph, but you will care about using video to make your professional life easier and more streamlined.

In the meantime if you have questions about BenchFly, want to comment about the site, or feel compelled to claim that “Fargo” was mediocre at best (you’d be wrong, but feel free to say it), check us out on Google+ or drop me a line on Twitter.

David received his PhD in Cell Biology from Vanderbilt University, and joined the BenchFly team in March, 2013. David’s interests lie in helping scientists at all levels communicate and market their work to colleagues, the public, potential customers, and that guy down the street who keeps asking about string theory. On the side, David is an avid runner, an occasional cyclist, and a home coffee roaster.

]]>

Dear Dora,

Dear Dora,

Everyone in my new lab pours all sorts of solvents down the drain and says it’s ok because they flush with a lot of water. I’m a first-year graduate student so maybe this is how all labs work, but it seems crazy. Is there a way for me to bring this issue up without being the annoying newbie?

– anonymous, first year graduate student

Dear Anonymous Graduate Student,

You are right to be concerned about others pouring solvents down the drain. Besides being an environmental hazard, your university can get fined thousands of dollars by the environmental agencies. Some labs even get shut down for improper disposal of lab waste.

It is true that some chemicals can be poured down the sink if you flush it down with plenty of water. If you know which chemicals are used, I recommend doing a quick internet search to determine if they are being disposed of properly (this will save you embarrassment when you bring up the issue). If you have a reasonable suspicion that there is improper disposal, you can bring it up politely, with the responsible person first. You can be polite such as “Are you sure this is the right way to dispose of XYZ?” If he/she dismisses your comment, then the most politically correct solution would be to bring it up with your PI (without any names). He/she might recommend a group meeting where you review proper chemical waste management, or call someone from the university to give a training (these are done on a yearly basis anyway).

Keep in mind that if you bring it up with your supervisor, he/she might give you the responsibility of being the lab safety officer. However, as a first your student this could be a good opportunity for you to learn more about the chemicals used in your field. In addition, your supervisor will view you as someone with initiative and leadership skills, and have more respect for you.

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

Dora Farkas, Ph.D. is the author “The Smart Way to Your Ph.D.:200 Secrets from 100 Graduates,” and the founder of PhDNet, an online community for graduate students and PhDs. You will find links to her book, monthly newsletters, and discussion board on her site. Send your questions to DearDora@benchfly.com and keep an eye out for them in an upcoming issue!

Stay tuned for the next Dear Dora in two weeks! In the meantime, check a few of Dora’s recent posts:

- The Conferencation: Adding Personal Time to a Scientific Meeting

- Keeping Preliminary Results Private with an Overexcited PI

- How Long is Acceptable for Holiday Vacation?

- Graduate School: How Long is Too Long?

- Is a Parasitic Postdoc Trying to Steal Your Project?

- Is the NIH Minimum Binding for All?

- Backing Out of a Postdoc Offer for a Better One

- Managing Publication Jealousy in the Lab

- Debriefing the Lab After a Scientific Conference

- Music in the Lab: MyTunes, iTunes, or No Tunes?

- Cell Culture Derailing Your Vacation Plans?

- Is a Publication Gap on Our CV a Job Killer?

Submit your questions to Dora at DearDora@benchfly.com, or use the comment box below!

We recently reconnected with our friend, Eva Amsen Ph.D., and found that in the time since our last conversation she’s moved on to a new job (congrats!). Her new position at Faculty of 1000 has thrown her right in the middle of a topic many scientists are very interested in–the future of scientific publishing. In a world of ever-increasing numbers of journals and lower technological barriers to information sharing, it’s unclear whether most publications will survive. We recently spoke with Eva about her views on the future and how the fear of getting scooped may be a driver for a new model of publication.

We recently reconnected with our friend, Eva Amsen Ph.D., and found that in the time since our last conversation she’s moved on to a new job (congrats!). Her new position at Faculty of 1000 has thrown her right in the middle of a topic many scientists are very interested in–the future of scientific publishing. In a world of ever-increasing numbers of journals and lower technological barriers to information sharing, it’s unclear whether most publications will survive. We recently spoke with Eva about her views on the future and how the fear of getting scooped may be a driver for a new model of publication.

1. BenchFly: Since we last collaborated to create a Group Meeting Bingo board for Developmental Biologists, there have been some exciting changes in your life!

Amsen: Yes! I had fun setting up the Node and providing an online space for developmental biologists, but I wanted to work with a broader group of scientists – beyond developmental biology and stem cells – so I moved to F1000Research, where I get to work on a journal that’s doing interesting things for all life scientists.

2. Based upon your recent experience, do you have any advice for other scientists on finding opportunities away from the bench?

If you’re at the bench now, and know that you want to find a job outside of research, start doing some of that work on the side right now. I know lab work is time consuming, but if that’s all you do, then that’s going to be all that you *can* do. I did a lot of blogging and science writing on the site, which proved useful, but other people might be interested in public engagement activities, or editing papers for friends, or even starting up a company on the side. If you really want to do these things, it will be fun to you, and you can find time for it.

3. Many folks looking to leave the bench worry that their years of scientific training will essentially be lost when they walk out of the lab. What skills, if any, do you feel prepared you well for your new position? Conversely, what have you found to be challenging?

The main translational skills that I picked up in the lab are probably time management and project planning. If you’re dealing with live cells that need attention every 48 hours, and thesis deadlines, and papers to grade, you get very good at determining what needs to be done to get everything finished on time!

The most difficult thing for me after leaving the lab has been that I don’t always enough time to think and process. I think I miss incubation times, where an experiment is just running itself for an hour or so and you can do something else without delaying your work. Now, if I sit and think for an hour, I’m an hour behind on my work!

4. We theorized that at some point in the not-too-distant-future, journals will no longer be the primary mode of scientific publication and over 70% of scientists thought that would be in the next 20 years. However, there are a number of innovative new publication models emerging. How do you see the future of scientific publishing?

I can see journals disappearing slowly. Journals come from a time when periodical print publishing was the best way to get your work out there, and that has now become a slow and static process compared to the much more flexible internet. There are entire fields within physics where researchers don’t publish in journals anymore, but just upload their work to ArXiv. In the life sciences we’ve been more conservative, but here, too, people are starting to publish a lot of their work outside of journals. Figshare and institutional repositories are getting large amounts of data that might not otherwise be published anywhere, but now is out there, ready for others to see. That just wasn’t possible in the 17th century, when the first scientific journal was published. Many new journals take full advantage of the fact that they don’t have to deal with print issues: they can accept all sound science, link and embed material within the text, track article level metrics, publish non-static articles, include referee reports and accept comments. Journals are starting to look less like journals, and more like interactive websites, so I can see that we’re in a transition phase, where eventually “journals” with periodical issues will become redundant.

5. Beyond the emergence of alternate platforms for sharing results (lab website/blog, etc.) the last decade has seen an explosion in the number of journals. F1000 has also launched a journal, F1000Research – what made F1000 decide to jump into the publication arena and what makes this journal different from the hundreds of other publications out there?

Technically, the company has previous publishing experience: F1000’s founder, Vitek Tracz, also founded BioMedCentral, the very first open access journal. F1000Research is effectively the next step: first it was open access, now it’s open data and open refereeing.

The biggest difference is that F1000Research does transparent post-publication peer review: articles go online after an in-house check, and the peer review doesn’t start until after the article is published. On any given article you can see if it has been reviewed yet, if authors have revised it, and even the full referee reports by invited reviewers – and their names! By publishing before review, research can get out there much faster.

Another difference is that authors can always update their paper – not just in response to reviewer comments, but also if they did some more experiments that they’d like to add to support the paper, or to update a literature review with a summary of new work. Those newer versions of the paper are linked to the old one, so you can always find the latest updates.

6. Speed is definitely important–anyone who’s ever worked in a lab is familiar with the idea of getting “scooped”—or seeing their work published by another group before they publish theirs. In fact, as a graduate student I had a paper held up for nearly at a single journal—not exactly relaxing times. Was this the major driving force for establishing the journal?

It was one of the main driving forces. (Openness — of data and referee reports as well as the paper itself — was probably the biggest one). The fact that we can publish an article within days of submission has definitely been a driving force for some of the authors who submitted to F1000Research. If you know a competitor is working on the same thing, it can be extremely stressful and disappointing to then get scooped as a result of delays by editors and referees. With F1000Research you might still have to wait for the referees (and articles don’t get indexed in PubMed until after they pass peer review), but in the mean time, the work is out there, and you can prove that you did it first. It’s also really useful if you have a grant deadline coming up: you don’t have to say “manuscript submitted” or “under review”, but you can link to the actual paper.

7. We live in a short attention span society, where thoughts longer than 140 characters seem burdensome… So if you were walking past a scientist in a hallway and had to blurt out one sentence as to why they should consider publishing in F1000Research, what would you say?

If we were running quickly and I had *very* little time to talk, I would steal the title of a blog post that Jeffrey Marlow at Wired science used to write about F1000Research: “Publish first, ask questions later”

If I had a bit more time, and could use a full 140 characters, twitter-style, I’d say “F1000Research uses a transparent post-publication peer review system, so you can publish within a week, and see signed referee reports later” (That’s exactly 140, although without punctuation…)

8. Since we’re still sweating over the stressful memories question 7 elicited, we want to open the final question up to everyone since we’re curious how many people share our anxiety (or if we’re just neurotic…).

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

Eva holds a PhD in Biochemistry from the University of Toronto, and is interested in all aspects of communication between researchers, from hallway conversations to academic papers. Before joining F1000Research, she launched and ran several initiatives for scientists to connect with each other and the wider community, such as the Node and SciBarCamp.

Leading image courtesy of F1000 Research.

]]> While nearly all of us face challenges during our postdoctoral years, we often feel alone in our struggles. In this series, we hope to share encouraging and uplifting stories of how other scientists were able to turn their situation around and move forward, despite a non-ideal situation. Like snowflakes, fingerprints, and nightmares, every postdoctoral experience is unique, so today we share the Postdoc Story of another successful scientist.

While nearly all of us face challenges during our postdoctoral years, we often feel alone in our struggles. In this series, we hope to share encouraging and uplifting stories of how other scientists were able to turn their situation around and move forward, despite a non-ideal situation. Like snowflakes, fingerprints, and nightmares, every postdoctoral experience is unique, so today we share the Postdoc Story of another successful scientist.

.

I. The Story

In grad school I was an immunobiologist. As a postdoc I studied neuroimmunoregulation. Now, I’m just starting a one-year research fellowship as a prelude to becoming a faculty member in my hometown university. After completing my degree, I was motivated to do a postdoc because, coming from a developing country, training in a first world institution is an advantage in the search for an academic position. In selecting my postdoctoral lab, I based my decision on the lab research projects, they suited my interests, the lab also had a good publication record and funding was not a problem, and the opportunity to live and work in Europe was a plus.

Going into the postdoc I wanted to learn new techniques, expand my network, increase my abilities as a scientist and improve my CV with high quality publications. On the road to pursuing my goals, I didn’t imagine I would start and build a project just to be left out of it at the end of my fellowship.

II. The Situation

Actually, I didn’t realize things were not as perfect as they seemed on the surface until the last leg of my fellowship. Before that I was pretty happy for the most part–I had excellent lab mates and was living in a great European city. Shortly after my arrival my PI asked me to start a project involving an animal model. I of course complied even if this meant changing projects from the very beginning and spending a lot of my time doing technician’s work. Working along a grad student we managed to get a lot of data and the project was expanding–more experiments, and more people got involved. I got so caught up in the work that I barely noticed my 2-year fellowship was about to come to an end. I then decided it was time to have a talk with my PI about it; to my shock, I was given 3 months to finish whatever I could and return to my country. I couldn’t believe I was being let go like that. I thought my work was valuable and important for the project; I was in charge. I was later offered the possibility of returning to the lab after staying a few months in my home country, however this was small consolation given that I was about to dismantle my entire life there to return to my country without a job or publication.

III. The Emotions

I spent the remaining months of my fellowship not only burned-out but also sick. I got anemic and I’m not sure how it happened, but I suspect it had a lot to do with how terribly stressed I was. The worst parts were the feelings of rejection and failure left by the situation but the lack of productivity was also painful. In theory, I obtained enough data for several publications, but nothing was published. After my departure and subsequent decision to not return someone else took over and first authorship is no any longer secured for me. It’s the way of the game, I’m afraid.

IV. The Solution

The way I saw it there was nothing I could do, I was being let go and wasn’t in a position to force anything. I also wasn’t interested in looking for another job just for the sake of staying in Europe. Regarding the publications, it’s all in the air, I don’t know what’s going to happen with that, and I feel powerless, to be quite honest. Despite all of this I kept going; I looked forward, even If was exhausted, depressed and insecure about my abilities as a researcher. Eventually, after my return to my home country, I got the support of senior researchers at my old school and successfully applied for a fellowship that will land me in a faculty position a year from now. All in all, I only spent two months unemployed. I guess we can say I was lucky, for now. I am aware that the road to become an established researcher is long and difficult and there is no guarantee.

V. The Lesson

I think the most important thing I learned was about me. At some point I was convinced I didn’t have the desire to keep doing science, I was wrong. I also learned, after all the monologues my friends had to endure, that I didn’t really want to be a postdoc anymore and that the way to have some control over your work–and its publication–is by being as independent as possible. You need to be careful to not get sucked into the postdoc mentality or you could risk getting stuck in postdoc limbo forever, stalling your career, especially if you are already in your mid-30’s. I would advise: 1) stick to your needs not those of your PI or the project, especially if you’re working under a fellowship, and 2) never forget that postdocs are temp positions–there’s always someone waiting to fill your position.

Want to hear another story?

- Marketer at a Scientific Publisher

- World Traveler

- Research and Application Scientist

- Junior Faculty Member

- Start-up Company Scientist

- Staff Scientist

.

Do you have a Postdoc Story you’d like to share? Email us to let us know.

]]>

Dear Dora,

Dear Dora,

I am currently half way through my Ph.D. Recently a new Ph.D. candidate joined our group. She is 35 this year while I’m in 25. She used to be a lecturer in another private university. She always bragged and boasted about her knowledge and achievements prior to joining our team. But then again, things turned out rather differently. She doesn’t seem to have basic lab skills like using the pH meter and unable to use some common sense in doing everyday work. In our culture, the older ones want respect from the younger ones but they don’t understand respect is something to be earned. The new Ph.D. student is also very egoistic despite her lack of experience in labwork but she constantly needs us to teach her. Some of the instruments were spoilt due to her negligence and her reluctance to ask–how should we deal with her? How do we deal with “juniors” who are very much older than us, in terms of age. I have been working in the lab for 3 years so I have a few publications which clearly demonstrated my ability while she has none. In certain ways I feel she is jealous of my achievement. What can I do? How can I improve the situations without hurting her feelings?

-Anonymous

.

Dear Anonymous,

It is not unusual for older students to feel insecure, precisely because of their age. She might feel embarrassed that she is older than the graduate students and maybe even the postdocs. That is most likely the reason that she keeps trying to prove herself. As a former lecturer, she probably has a basic understanding of science, while being rusty on the lab skills. My recommendation is tell her clearly what she needs to know, without being condescending. For example, if she ruined an instrument because she neglected to do maintenance, let her know how important it is to do the maintenance to make sure others can do their work. Everyone likes to get along with their coworkers, and she probably needs only a few warnings to make sure she will do her work correctly. She is also more likely to respect your opinion if you build rapport with her by including her in lunches and other group activities.

.

Dora Farkas, Ph.D. is the author “The Smart Way to Your Ph.D.:200 Secrets from 100 Graduates,” and the founder of Grad School Net, an online community for graduate students and PhDs. You will find links to her book, monthly newsletters, and discussion board on her site. Send your questions to DearDora@benchfly.com and keep an eye out for them in an upcoming issue!

Stay tuned for the next Dear Dora in two weeks! In the meantime, check a few of Dora’s recent posts:

- Using Your PhD Outside of Research

- The Conferencation: Adding Personal Time to a Scientific Meeting

- Keeping Preliminary Results Private with an Overexcited PI

- How Long is Acceptable for Holiday Vacation?

- Graduate School: How Long is Too Long?

- Is a Parasitic Postdoc Trying to Steal Your Project?

- Is the NIH Minimum Binding for All?

- Backing Out of a Postdoc Offer for a Better One

- Managing Publication Jealousy in the Lab

- Debriefing the Lab After a Scientific Conference

- Music in the Lab: MyTunes, iTunes, or No Tunes?

Submit your questions to Dora at DearDora@benchfly.com, or use the comment box below!

.

]]> Dear BenchFly readers,

Dear BenchFly readers,

I’ve been absent for far, far too long, and before anything else, I’ll need to apologize for that. This new Enzyme Corner article will thus serve a dual-function: 1) telling a new enzyme/protein story, which is far overdue, and 2) bringing you up to speed on what I’ve been up to lately.

.

For those who came in late…

Because it’s been ages since I last wrote for BenchFly, before I tell you what I’m up to now, let me give you a bit of a 5-year summary of where I’ve been and where I am. Five years ago, in June 2008, I was wrapping up my PhD thesis in the Storey Lab at Carleton University in Ottawa, where I studied, in the grand scheme, the molecular mechanisms of cryobiosis; I looked at important metabolic and signaling enzymes in the freeze-tolerant frog, Rana sylvatica, the hibernating Richardson’s ground squirrel, Spermophilus richardsonii, and sometimes poked around with other animals too. At the end of August 2008, I then moved to the Benkovic Lab at Penn State, where I researched for the following 2 years the regulatory controls involved in the reversible assembly of the purine biosynthetic enzyme complex in HeLa cells. Following this, I returned to Montreal, where in August 2010 I began a fellowship known as the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council-Industrial Research and Development Fellowship (NSERC-IRDF) at a startup biotech company called Micropharma Ltd. Here, I worked on various aspects of disease-targeted probiotics that were rich in the activity of key metabolic enzymes. I also contributed to the development of an enzyme-driven, nitric oxide-generating medical dressing with antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activity.

Now

Since July 2012, I’ve been at Mount Allison University, the Maclean’s magazine-ranked top primarily-undergraduate university in Canada for 16 out of the past 22 years. I hold the position of the Margaret and Wallace McCain Postdoctoral Fellow, which is actually a bit closer to faculty than the word “postdoctoral” would have you believe. I teach a half-course load, having taught a 4th-year biochemistry course called Immunochemistry last Fall semester, and another 4th-year biochemistry course called Signal Transduction over the Winter semester. For this coming Fall semester, I’m developing a brand-new, never-before-taught 3rd-year biochemistry course called Toxicology.

I also get to participate in research activities, and though the limited-term nature of the 2-year position doesn’t allow me a research infrastructure of my own, I do get to collaborate with faculty who share interests similar to my own. Best of all, as of May, I am now a full-fledged supervisor of my first two very own undergraduate honors thesis students.

As far as research goes, I’m once again back in the domain of comparative biochemistry and physiology, relying on animal models and focusing on metabolic regulation of stress physiology, with a bit of twist: this time around, the stressor is not cold or other naturally-occurring environmental phenomenon, but rather, a man-made toxicant. That toxicant is the spherical nanoparticle.

Nanoparticles

Finally, on to the science! There’s a lot I could say about nanoparticles, but as a biochemist/physiologist, even I’m forced to admit that much of it could be better-said by a materials scientist. For the interests of this article, in a nutshell a nanoparticle can be composed of a variety of elements, both metallic and/or nonmetallic. They are colloidal assemblies of that/those element(s) at the nanoscale- smaller than micrometers but larger than picometers. Because of the way these nanomaterials are assembled, their surface area to volume ratio, and their varieties of surface coatings or functionalizations, they have unique properties; the properties of the colloids are different from the ionic or molecular versions of their constituents (also known as the “bulk” constituents), and also different from the macroscale, solid forms of these materials as well.

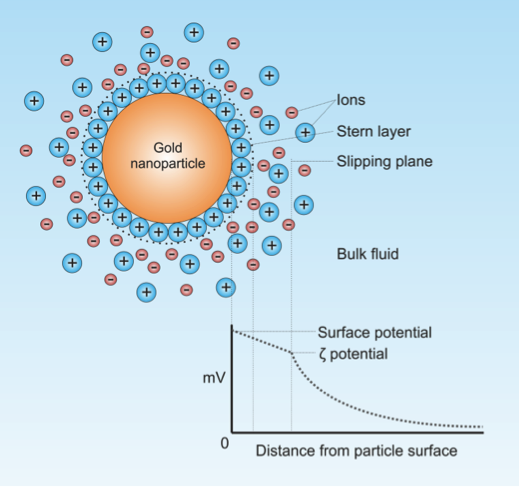

Overall, because nanoparticles are roughly on the same scale of a protein’s size, they tend to interact with proteins… and not in a good way. In order to keep nanoparticles in suspension and keep them from agglomerating (or “clumping”) their surface coatings are often charged, allowing them to accumulate bilayers of ions from whatever fluid (biological or otherwise) in which they happen to be suspended (see Figure 1). When they are, indeed, suspended in biological media, the ions they accumulate are not only simple ionized atoms (Na+, K+, Cl–, etc.), but also proteins replete with their own electrostatic surfaces (aspartate, glutamate, lysine, arginine, histidine). A nanoparticle will eventually gather a collection of proteins interacting with its surface, which is becoming more prevalently known in the field of nanotoxicology as a “protein corona.” Proteins can interact reversibly with the nanoparticle surface, associating and dissociating if the interaction is weak enough. Given enough time and the right proteins, however, some proteins may adsorb more strongly to the nanoparticle surface than others, forming a tighter and overall a more irreversible association.

Fig 1. Depiction of a gold nanoparticle and the layers of ions formed around it that allows it to remain in suspension. (Source: Wikipedia, Creative Commons)

The protein

Many scientists in the field of nanoscience study the effects of these protein corona from the perspective of the nanoparticle. How does this change the surface physical and chemical properties of the nanoparticle? How does this affect the disposition (distribution, biotransformation, and excretion) within a living organism? And so on and so forth. However, these questions essentially ignore the co-star of the nanoparticle-protein interaction. In other words, what about the protein?

Well… think about a protein in its native conformation, in its native (and unperturbed) environment. Now… think about that same protein “stuck” (in some way, shape, or form) to a nanoparticle. Through electrostatic interactions, through Van der Waals forces, perhaps to other proteins that are also associated with the nanoparticle like links on a chain, this association is clearly not a natural one, as ionic or other side-chains on the protein are stretched or compacted in their complex interaction with a nanoparticle.

Needless to say, while a protein may not be outright denatured by its interactions with a nanoparticle, it is most definitely not in what we consider to be a “normal,” native conformation.

Structural-__________ relationships

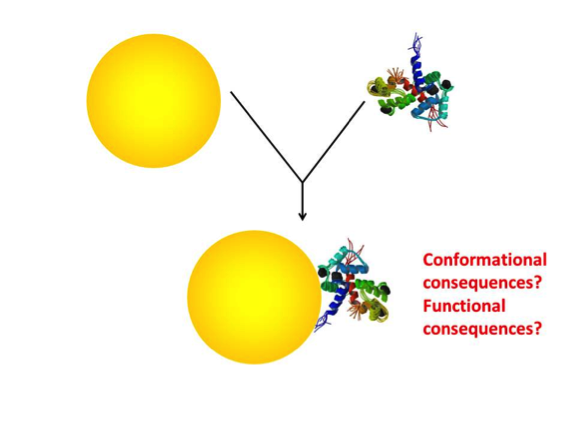

With most types of molecules or biomolecules that we study in the biological sciences, structure has a direct impact on function. And while the primary amino acid sequence doesn’t change, for all intents and purposes conformational changes are structural changes. If a protein is incorporated into a nanoparticle’s protein corona and its conformation is perturbed, you can make a fairly safe bet that its function is similarly perturbed (see Figure 2).

Fig 2. Depiction of a gold nanoparticle and a protein forming an association (the gathering of a “protein corona”) and the pondering of the associated conformational and functional consequences to the protein.

What function, however, are we talking about?

Well, that depends on the protein(s) that is/are interacting with the nanoparticle. Virtually any protein can interact with a nanoparticle, to a weaker or stronger degree, based on the localization of that nanoparticle within an organism. Thus opens the wide field of molecular mechanisms of nanotoxicology.

For instance, are we talking about:

- “Carrier” proteins of otherwise-insoluble ions biomolecules in the plasma?

- Proteins of the innate and adaptive immune systems in the plasma?

- Structural proteins in tissue and cell membranes?

- Catalytic proteins (i.e. enzymes) in mucus, bile, interstitial fluid, plasma or just about anywhere else?

- And then… if a nanoparticle happens to cross the plasma membrane and make its way into the intracellular environment… what happens to membrane, cytosolic, organellar, and nuclear components, protein or otherwise?

Pandora’s box

All the above focused on, for lack of a better term, the physical aspects of the interactions between nanoparticles and proteins. We’ve said nothing so far about the chemical properties of nanoparticles, of which there are many, particularly their generation of reactive oxygen species.

Next time, we’ll look at some more specific mechanistic examples.

Chris is originally from Montreal, and is a Comparative Biochemist and Physiologist. His educational and postdoctoral experiences have taken him from Montreal to Ottawa, State College (Penn State), and finally back to Montreal’s biotech industry. Presently, he is the Margaret and Wallace McCain Postdoctoral Fellow at Mount Allison University in Sackville, New Brunswick, Canada. He is researching the role of protein phosphorylation in physiological stress, and teaching 4th-year undergraduate courses in Biochemistry.

Chris is originally from Montreal, and is a Comparative Biochemist and Physiologist. His educational and postdoctoral experiences have taken him from Montreal to Ottawa, State College (Penn State), and finally back to Montreal’s biotech industry. Presently, he is the Margaret and Wallace McCain Postdoctoral Fellow at Mount Allison University in Sackville, New Brunswick, Canada. He is researching the role of protein phosphorylation in physiological stress, and teaching 4th-year undergraduate courses in Biochemistry.

What, you missed one of Chris’ previous articles?! Don’t worry, you’re just a click away.

- Make Up Your Mind! When Phosphorylation Turns Enzymes “ON” or “OFF”

- Phosphoproteins: Where’s the “ON” Switch?

- Is There Really Science in the Twitterverse?

- Know Your Role: Enzymes and Their Unexpected Physiological Functions

- Tearing It Up: Glycogen and Its Chemical and Biochemical Breakdown

- Enzymes and the Problem with Cosmo Kramer’s Levels

- What’s in a Name?

.

]]> Dear Dora,

Dear Dora,

Are there certain career paths outside of research where the PhD dramatically helps your career advancement? I’m a third-year grad student planning on leaving the bench (to do what, I’m not sure) but I feel like I’m half way there so if getting the letters is important I could tough it out.

—MM, grad student

Dear MM,

There are many alternative paths where a PhD would enhance your career advancement (see Q&A column below on administrative positions). Other careers include patent law, science writing, and regulatory jobs (e.g. working for the FDA). Many scientist positions in the pharmaceutical industry are away from the bench as well (e.g. project management, report writing). I listed several references below (including a group on LinkedIn) on alternative careers for PhDs.

If you are interested in these careers I recommend researching job postings, since some of these positions only require a Master’s Degree. In fact, I have a patent lawyer friend who left graduate school after five years (!) with a Masters Degree to go to law school. It is important to evaluate whether staying in graduate school is worth your time (for example, will you school give you a Masters degree if you leave early). My friend had a few publications already, so he had something to show for the time he spent in graduate school. Another friend of mine left graduate school after 2 years, but he already had a job offer for a position that only required a Bachelors.

Whether you decide to stay or leave it important to have a plan both for your finances and your career advancement. Employers will understand if you change your mind about earning a PhD, as long as you have the right skills, enthusiasm and commitment to your new career path.

If you have any doubts whether it is worth getting a PhD, visit our latest blog at:

http://gradschoolnet.org/2013/04/is-it-worth-getting-a-phd/

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.References

Articles on job search and alternative careers:

http://sciencecareers.sciencemag.org/tools_tips/outreach/events/2010_06_17

http://www.linkedin.com/groups/Alternative-PHD-Careers-3404777/about

.

Dora Farkas, Ph.D. is the author “The Smart Way to Your Ph.D.:200 Secrets from 100 Graduates,” and the founder of Grad School Net, an online community for graduate students and PhDs. You will find links to her book, monthly newsletters, and discussion board on her site. Send your questions to DearDora@benchfly.com and keep an eye out for them in an upcoming issue!

Stay tuned for the next Dear Dora in two weeks! In the meantime, check a few of Dora’s recent posts:

- The Conferencation: Adding Personal Time to a Scientific Meeting

- Keeping Preliminary Results Private with an Overexcited PI

- How Long is Acceptable for Holiday Vacation?

- Graduate School: How Long is Too Long?

- Is a Parasitic Postdoc Trying to Steal Your Project?

- Is the NIH Minimum Binding for All?

- Backing Out of a Postdoc Offer for a Better One

- Managing Publication Jealousy in the Lab

- Debriefing the Lab After a Scientific Conference

- Music in the Lab: MyTunes, iTunes, or No Tunes?

Submit your questions to Dora at DearDora@benchfly.com, or use the comment box below!

.

]]>