Once in a while we all have to face the interview gauntlet. Granted, grad-students and post-docs go through interviews as often as white Christmas in Hawaii… Ok, maybe not as rarely as in white Christmas in Hawaii but these particular groups interview on average every 4 to 5 years. Once you realize that there is an interview looming in the near future, you probably try to brush up on your interviewing and people skills. One intriguing aspect of the interview etiquette is that it can closely resemble an animal planet episode that describes courting rituals among birds. Yes, there are many unspoken rules, many things that can create a favorable impression of you and many things that can ruin your chances of ever getting that job. One mystifying aspect of job interviewing I wanted to cover today is the infamous “Thank You” note.

Once in a while we all have to face the interview gauntlet. Granted, grad-students and post-docs go through interviews as often as white Christmas in Hawaii… Ok, maybe not as rarely as in white Christmas in Hawaii but these particular groups interview on average every 4 to 5 years. Once you realize that there is an interview looming in the near future, you probably try to brush up on your interviewing and people skills. One intriguing aspect of the interview etiquette is that it can closely resemble an animal planet episode that describes courting rituals among birds. Yes, there are many unspoken rules, many things that can create a favorable impression of you and many things that can ruin your chances of ever getting that job. One mystifying aspect of job interviewing I wanted to cover today is the infamous “Thank You” note.

Interview etiquette essential: The thank you note

So you managed to survive the interview and the employer tells you they will contact you in a week to update you on the interviewing process. What happens during this week? Complete radio silence? You wait for the call, a week passes, two weeks … could you have done anything to keep the communication open? Instead, you are frustrated and stressed… Ok, let’s not panic and just review one aspect of the post-interview etiquette called the “Thank You” note.

Firstly, what is this mysterious “Thank You” note and do you really need it? When you go for an interview, the employer looks for more than just your advertised job skills. They also look at how well you interact with people and how you fit in with the rest of the team. Having good manners and people skills is something that the potential employer looks for in each candidate. A Thank You note thus serves several purposes.

Show your manners and express appreciation for the interviewer’s time.

Simply, you send a “Thank You” note right after the interview to each interviewing member to express gratitude for the time they allocated to interview you. Interviewers have to re-arrange their working schedule to accommodate you, so be polite and show you manners. People like to work with well-mannered employees, considering that manners are becoming antiquated in this world.

It is a chance to re-assert your interest in the position.

Were you enthusiastic and excited about the prospects of working for that particular company during the interview? In case you had a mortified look on your face, this is your chance to stress why you are interested in the position.

It is a chance to emphasize why you are a good fit for this position.

Be aware that the same people will probably interview dozens of other potential candidates for the job. You want to make sure that they remember you. Send them a note that states precisely why you are a perfect fit for the job. Remember what it is you said to each interviewer and customize your card for each person. Mention what stood out in your memory specifically with that person.

It is a chance to clarify your responses.

Did you stumble during one of the questions? Acknowledge it in your note and clarify the answer. It can impress the interviewer that you actually took the time to figure out the right answer.

Keep you note brief and focused. Firstly, thank the interviewer for their time. Then re-affirm your interest in the position and state why you make a great fit for this job. Mention what it is they said that made you feel like this is the right company and the right job for you and why you are the right candidate for them. Lastly, clarify any questions and again thank them for the opportunity.

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll..

Yevgeniy grew up in New York, but decided to transplant himself to the West Coast for his PhD studies at the Scripps Research Institute, where he studied mechanisms of gene regulation in the immune system. Recently, Yevgeniy again found himself in New York City, pursuing a post-doctoral research project in oncology. Realizing that his true passion was writing, Yevgeniy decided to leave academia and pursue science writing as a freelancer to share his passion for fostering communication between the scientific community and the public. In his spare time Yevgeniy works as a Krav Maga self-defense instructor.

.

For more PhD Tales from the Couch, see Yevgeniy Grigoryev’s previous articles:

.

]]> Today’s doctoral programs continue to prepare students for a traditional academic career path despite the inadequate supply of research-focused faculty positions. At the same time, PhDs who decide to pursue a non-academic careers are somehow considered failures or sell-outs by the Ivory Tower. However, a gaping hole remains in this type of reasoning. The academic training has ignored the many trainees who will pursue non-traditional positions. The facts are undeniable, and as Meghan Mott masterfully demonstrates with a series of eye-opening and alarming facts in her article Careers in Traditional Academia: Outlook Bleak, academia simply has no room for the newly minted PhDs. As a result, the majority of PhDs will have to pursue non-academic careers.

Today’s doctoral programs continue to prepare students for a traditional academic career path despite the inadequate supply of research-focused faculty positions. At the same time, PhDs who decide to pursue a non-academic careers are somehow considered failures or sell-outs by the Ivory Tower. However, a gaping hole remains in this type of reasoning. The academic training has ignored the many trainees who will pursue non-traditional positions. The facts are undeniable, and as Meghan Mott masterfully demonstrates with a series of eye-opening and alarming facts in her article Careers in Traditional Academia: Outlook Bleak, academia simply has no room for the newly minted PhDs. As a result, the majority of PhDs will have to pursue non-academic careers.

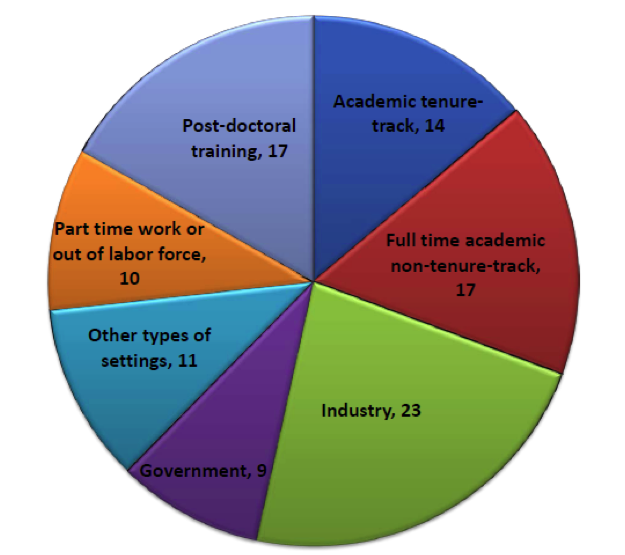

I can go even further to suggest that the term “alternative” can be applied to a career in academia, because since 2001:

< 20% of biology PhDs have been moving into tenure-track 5-6 years after receiving the degree (in 2006, only 14% these PhDs were in tenure positions)

43% are employed in non-academic positions:

- 23% in industry

- 9% in government

- And 11% in other types of settings

17% are employed full-time in non-tenure-track academic positions.

10% work part-time or are out of the labor force.

17% are still in postdoctoral training.

Figure: PhD career paths 5-6 years after receiving PhD (These data are from the 2006 National Science Foundation Survey of Doctorate Recipients, as analyzed by Paula Stephan (Stephan, 2012))

.

It is no longer possible to deny the fact that the majority of PhD recipients will have to look outside of Academia for employment, yet their traditional training does not necessarily reflect the job skills currently in demand on the job market. As a result, many new PhDs are forced to default into doing a series of post-doc fellowships, which may not necessarily increase their chances of getting a job they want (fewer than 1 in 5 post-docs will actually get a tenured faculty position!). It is becoming painfully clear that graduate training programs should be raising awareness about non-academic opportunities and what they entail. While it should be the incentive of graduate programs to educate students about possible career choices before they are thrown into the job market, in most cases, PhD students have to provide for themselves and look for such opportunities on their own. So, given that academic jobs are limited and the current graduate training does not prepare the majority of students for jobs outside of the traditional academic career, I think it would be prudent for every PhD student to think about their professional development while they are still in the midst of their graduate training.

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll.

.

Yevgeniy grew up in New York, but decided to transplant himself to the West Coast for his PhD studies at the Scripps Research Institute, where he studied mechanisms of gene regulation in the immune system. Recently, Yevgeniy again found himself in New York City, pursuing a post-doctoral research project in oncology. In his spare time Yevgeniy works as a Krav Maga self-defense instructor, and as a scientific writer to share his passion for fostering communication between the scientific community and the public.

.

For more PhD Tales from the Couch, see Yevgeniy Grigoryev’s previous articles:

Sharing PhD Tales from the Couch

.

]]>

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us …”

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us …”

This quote from A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens can perhaps sum up the feeling of anxiety we all experience at certain times, when our life flip flops between complete despair and a promise of success. This may be especially true if you are a graduate student or a post-doc dealing with work-related stress brought about by a number of factors. As someone in a trainee position at the start of our scientific careers in the academic or corporate hierarchy, we are no strangers to stress. We work in the environment loaded with anxiety triggers: sometimes we feel powerless working in a state of perpetual uncertainty and lack of control, always exposed to extreme competitiveness and limited resources, long working hours, failed experiments, harsh criticism from reviewers or committee members, unrealistic demands from the adviser, and let’s not forget the “Publish or Perish” formula of the Ivory Tower. An article titled Grad School Blues published in The Chronicle Review reports that “Graduate school is gaining a reputation as an incubator for anxiety and depression.” As such, we are chronically exposed to anxiety triggers.

.

Anxiety is a natural response

So what is the answer, you might ask. Should we sacrifice graduate education and a career in science to avoid all this anxiety? For those of you who, after reading this article, decided to say goodbye to your graduate career, STOP! This, of course, is not what I am suggesting. Anxiety is a part of life and a natural response that by itself it is neither good nor bad. However, it is how we react under such situations that determines our ability to withstand stress. In fact, when faced with a challenge some anxiety is actually advantageous, because it provides the necessary push to work harder under duress. This is because anxiety is an ancient survival mechanism inherited from our ancestors: the fight-or-flight reflex. If not for our ability to increase performance under stress, human species might have never outlived cyber-toothed tigers or the ice age. However, our ancient survival system has not quite caught up with the modern world. Sometimes, triggers that are not necessarily life threatening, like presenting data to an audience or stress associated with a lack of job prospects, can eventually induce a chronic state of anxiety and diminish our work efficiency. Our inability to fine-tune the anxiety response eventually nips away at our resilience in the face of everyday challenges, leading to depression. With time, such stress can wear out our enthusiasm and mental state, leading to a state of “tunnel vision” in the workplace. Just remember how excited and idealistic you were when applying for graduate school? Now fast forward to year 4 or 5 of your grad school experience … do you feel disgruntled and lack purpose? This dangerous trend and high burn-out rates, combined with a feeling of perpetual transition and instability, can sap even the most resilient and the brightest.

.

How to deal with anxiety

So, if anxiety is a built-in response and can actually be helpful in moderate doses, we can do anything not to succumb to the downward spiral? How do we minimize anxiety and develop resilience to shake off work-related stress? While we may not control the factors that contribute to anxiety, we can try to be in control of how we react to and handle them. Here I am providing some advice on how to handle anxiety:

1) Minimize anxiety by setting achievable short-term goals. It does not hurt to plan far into the future. However, it is very helpful to plan bite-sized achievable goals that you can accomplish in a week, or a month. This way you will feel that you are making progress and identify areas that require more of your attention. This approach helps you feel more productive and positive when you achieve these goals, without setting yourself up for a long-haul goal that might not yield results.

2) Taking care of yourself and feeling positive is essential to the mental and physical health. Exercises is a good way to invigorate yourself, release stress, clear your head, and re-focus mentally because during exercise our bodies release endorphins that provide a natural boost of positive energy. For example, during my graduate studies I started training in Krav Maga, a very rigorous and practical self-defense system, which did wonders because it allowed me to refocus my mind from work-related issues and feel positive and re-energized (not to mention that I learned self-defense and improved my confidence!).

3) Establish work-life balance and change pace. We need to strive to establish a good work-life balance to avoid burnout. Taking breaks during the workday and going for walks can help prevent stress and tension buildup. Any sort of positive and reinforcing activity, such as travel, spending time with friends, hiking, going to a museum, etc, can help break up monotonous routine we sometimes face and combat anxiety.

4) Seek support from colleagues. Your colleagues may be experiencing the same stress and frustrations as you are, and may have found productive ways to cope and resolve them. You are not alone, and it helps to feel some solidarity and encouragement from your peers. You should not feel ashamed or embarrassed of what you are feeling, and reach out for peer support. There might already be support groups or networks established for this purpose. If not, then perhaps you can take initiate and organize a support group, which will address the work-related anxiety and also make you feel more positive and in control. However, it is important not to continuously dwell on negative emotions when sharing with your peers, because it could serve as an incubator for negativity and result in further demoralization and anxiety. Instead, try to be positive and supportive of other people, and you will feel positive yourself. Some institutions have complementary well-being and mental health services with trained professionals who address specific issues that scientists may have in the workplace.

5) Talk with your supervisor. Hopefully you are on friendly and professional terms with your boss, and they actually care about your well-being. It is important to talk to your supervisor if you feel unhappy about your current project or work direction. Often, they may be able to provide you with the perspective you need to feel like you are doing a better job, or redirect your efforts so that you feel more productive

6) Do not beat yourself up. It may turn out that much of your stress is self-imposed. Are you setting yourself up for unrealistic expectations? Are you pushing yourself too hard and not acknowledging your accomplishments? Refer to advise #1 on setting up achievable short-term goals. It could be that you are being too tough of a self-critic and cause your anxiety by never being satisfied with your work. Do not destroy your self-confidence by constantly denigrating yourself, but instead reward yourself for getting things done. We can ruminate on negative thoughts and thus breed anxiety in our minds. Do not beat yourself up for making mistakes, we all make them, and remember to move on and focus on what is at hand.

7) Identify the causes of your anxiety. Think carefully about what it is that is causing you to feel anxious. Is it anything that you can change? Is there anything that you can change about yourself to avoid feeling this way? You cannot worry about things over which you have no control. You may realize that some things you worry about are not problems at all, but rather that your mind just tends to over-think them and cause you to feel anxious. Ask yourself if you are getting as much satisfaction from your work as you once did and if you are as productive as you once were. If after realistically assessing your job satisfaction and workplace productivity, you determine that you are really unhappy and your goals are unattainable, then perhaps either your work setting is toxic, or your attitude is incompatible with the current work setting (or both). In this case you should seriously think about changing your line or place or work. To avoid anxiety and work-related burnout, you should do what you love, which would allow you to grow as a person and feel positive about what you do, rather than causing you more pain and anxiety.

8) Avoid negativity. Avoid spending time around negative people, they are like black-holes for your well-being and will drain you of positive energy. If certain settings and people cause you to feel negative, minimize your exposure to them. Anything that causes you to feel negative emotions will only exacerbate your anxiety. This also extends to interactions outside your work, including personal relationships. You will end up bringing this negativity with you to work, which is likely to make you feel more stressed and susceptible to anxiety at work. Same goes for any other sources that make you feel negative: news, TV, etc. Instead, try to spend time with people and visit places that make you feel positive and energized, as mentioned in advices 2, 3, and 4.

Hopefully these 8 simple suggestions will help you fight off and overcome anxiety issues that we face every day. Since I started this article with a quote, let me finish it with one: “Drag your thoughts away from your troubles … by the ears, by the heels, or any other way you can manage it.” – Mark Twain

.

Note: There is a poll embedded within this post, please visit the site to participate in this post's poll..

Yevgeniy grew up in New York, but decided to transplant himself to the West Coast for his PhD studies at the Scripps Research Institute, where he studied mechanisms of gene regulation in the immune system. Recently, Yevgeniy again found himself in New York City, pursuing a post-doctoral research project in oncology. In his spare time Yevgeniy works as a Krav Maga self-defense instructor, and as a scientific writer to share his passion for fostering communication between the scientific community and the public.

.

How do you manage anxiety in lab?

.

]]> Editor’s note: Obtaining a PhD is undoubtedly an intellectually challenging endeavor. However, many of us are unprepared for the extent of the mental hurdles we face on the road to our degree. Stress, loneliness, panic, anxiety, uncertainty, and depression are commonplace in most scientists’ career development at some point, yet these emotional struggles are rarely discussed openly. Couple this with the fact that many researchers find their work and sacrifices unappreciated by family, friends, and society at large and the strain can become overwhelming. At times it feels as though we’d benefit more from a therapist than from a PI.

Editor’s note: Obtaining a PhD is undoubtedly an intellectually challenging endeavor. However, many of us are unprepared for the extent of the mental hurdles we face on the road to our degree. Stress, loneliness, panic, anxiety, uncertainty, and depression are commonplace in most scientists’ career development at some point, yet these emotional struggles are rarely discussed openly. Couple this with the fact that many researchers find their work and sacrifices unappreciated by family, friends, and society at large and the strain can become overwhelming. At times it feels as though we’d benefit more from a therapist than from a PI.

Today we’re excited to announce our newest contributor, Yevgeniy Grigoryev, Ph.D. who will shed light on many of the shared challenges we face as scientists. In ‘PhD Tales from the Couch’ Yevgeniy will seek experiences from the broader community in order to identify solutions to help researchers move forward. We recently spoke with Yevgeniy about the roots of his passion for helping fellow scientists, the challenges he faced in his own career development and what’s at stake for science education if we don’t address the problems now.

BenchFly: As a kid, did you always know you wanted to be a scientist, or did that decision come later?

YG: As a kid, I demonstrated abundant curiosity for the world around me. I enjoyed asking questions, solving problems and tackling riddles. I think I just really wanted to know what made things work. I disassembled alarm clocks, old TV sets, anything that could tick, chime or beep and then tried to put it back together … the best I could. When I was 8 or 9, my parents bought me a small light microscope, and that’s when my foray into science began – I wanted to know what color eyes ants had, what happened when you dissolved different substances in water, if my dog could dream and what he dreamt about, etc. I did not think of this as a profession, it was just natural to want to know how things worked. I did not think too hard about what I would do when I grew up, I was too busy trying to piece back together my parent’s alarm clock.

Entering graduate school, did you have a particular career path in mind?

Entering Graduate school, I was such a visionary! I had everything planned out about how I will change the world and cure all the diseases, and become world famous for re-introducing space food to the public. Don’t we all feel this way when starting grad school? Honestly though, while in college, I was divided between a career as a medical doctor and a research scientist. Both were viable options. By then I had already developed a healthy fascination and interest in science. There were other subjects that I enjoyed as well, such as History, Literature, and Writing. But what really motivated me was my desire to be useful in this society, to help people around me, to make the old young again and the sick healthy and other such noble things. Yet, as I helplessly watched my grandmother succumb to the Alzheimer’s disease while the medical field was powerless to reverse the neurodegenerative damage it inflicted on her, I decided to choose a career of a research scientist, which seemed to me the most practical choice would enable me to address such challenges head on. I also realized that I wanted conduct research more on the clinical side (sorry, basic science, we had some good times, but it’s not you, it’s me … really!). I arrived at this conclusion after realizing that approximately 80% of my time in the lab, I transfer microscopic amounts of liquid from one tube to another, day in and day out. In order not to go crazy, I had to have a bigger picture in mind. That bigger picture to me is addressing current clinical issues, like investigating the immune mechanisms of organ transplant rejection, focusing on developing targeted cancer therapies, or promoting science communication between various sectors of society.

Yevgeniy Grigoryev, Ph.D.

Looking back on your experience at Scripps, what do you think were the most valuable components of your graduate education?

I think the most valuable component of my graduate education was that it was unlike any other education I was used to. Most of the things that I learned in grad school were not taught in classes (which were few and not directly relevant to my research), or textbooks. The most valuable components involved developing an independent mindset, to be able to face questions that did not necessarily have answers, to dare to propose experiments even though they might fail. I think this was precisely it, not to be afraid to fail! In this world, we are all judged by our successes, and failure carries such a heavy stigma of shame. But in graduate school, failure was the driver leading to success. To quote the 1969 Nobel prize winner in Literature, Samuel Beckett, “Try again, fail again, fail better.” I learned more about the field, experimentation, and asking the right questions after my experiments failed (which happens 70-80% of the time … ever wonder why it takes 5 to 6 years to get that PhD?).

More importantly, in this unique and seemingly unstructured environment I learned a lot about myself. I would not be able to do it on my own, of course. I had the invaluable guidance of my colleagues, my graduate adviser, and my thesis committee, who challenged me, encouraged me, and occasionally criticized me (constructively, of course). Troubleshooting, learning on my feet, and thinking outside the box were just some of the skills I developed in graduate school, in addition to becoming more resilient, resourceful, and analytical in my thinking … but enough self accolades!

…and what were some of the pitfalls?

To me, the biggest pitfall in graduate school was feeling more and more alienated from the world around me. As I spent more time at the bench and increased my specialization, the fewer and fewer people around me understood, cared to understand or even bothered to understand what it is I did or why I did it. Such narrow path of specialization can make it hard for you to communicate with the rest of the world, which requires generalization. I was so used to dwell in the details of my PhD project that I lost touch with the outside world (world outside the lab, that is). This became especially noticeable when I started writing my dissertation. My friends would ask me what my work was about and I would immediately bombard them with such rods as “Genome-wide analysis”, “differential gene expression”, “post-transcriptional gene regulation”. They would quietly listen, pat me on the back and be on their way to find someone with whom they can actually have a conversation. So my biggest fear became that after so much hard work and time spent researching my project, my thesis would only be seen by a handful of people in this world: my graduate adviser, the three members of my graduate committee, and maybe a handful of graduate students who cite my work in their abstract. Isn’t it a shame that almost no living soul would care to open these pages that were saturated with my proverbial sweat, lack of sleep, and excess of caffeine? And just to think that my finest intellectual achievement would gather dust in the archives of some library until the sands of time have claimed its existence forever!

Another challenge that I became very aware of while in grad school was the question of what I should do and what path I should take once I graduate. Graduate School tends to make you feel very sheltered from the outside world. While my friends on the “outside” were getting laid off, looking for new jobs, going through the interviewing circuit and learning the ropes of what it takes to actually get a job, I was comfortably pipetting at my bench. Afterall, this is what is expected of you in grad school: you work hard, get your work published, write and defend your thesis and be on your way. The problem is, as I realized too late, is where exactly am I supposed to go with all these skills that I learned? I was too busy working and writing to actually stop for a second and imagine where I want to be once this is all done. Do I want to continue with academic research and look for an academic post-doc? Am I interested in transitioning to Industry? What other aspects of science could provide an enjoyable career?

By asking these questions, I found a true passion for communicating science, for looking back at the big picture of why I do research. In order to communicate complex ideas and concepts, I had to become a generalist again, and find the common thread of humanity – something that unites us all and helps us relate to the big picture. In doing so, I also was able to think more about my life’s work and how it relates to the public good and common/personal good.

How do you think these challenges will affect the future of science education and research left unchanged?

Let’s admit it, no one wants to feel alone, alienated, and misunderstood in this world. We, as humans, have an inherent desire, nay, need to communicate, to tell stories, to relate to these stories (remember when you were just a kid and you loved listening to bedtime stories) … We simply love stories! With the current approach to graduate education, we are steadily producing hundreds of highly trained specialists each year. However, due to such rigid specialization, these highly trained PhDs may feel that they have lost that “common thread of humanity”. After all, let’s rewind back to when I was applying to Graduate School – I was young, full of zest and energy, ready to share my future discoveries and findings with the world. Now let’s fast forward 3 or 4 years into my graduate education – I feel like a castaway … “Wilson! Wilson! I’ll do all the paddling. You just hang on”. And then you start doubting yourself. Were you right to choose this path? Is it supposed to feel this way? Are you the only one going through such rocky experience? I think it is important to remind these young researchers that they do not have to become isolated on this course, that while there is a trend for specialization, we should always see the big picture in front of us … otherwise we are just highly trained liquid carriers.

What are your goals with PhD Tales from the Couch?

My goal with “PhD Tales from the Couch” is to connect people at different stages of the professional growth and specialization and create a portal where peers can shed some frustration, share a word of advice, stories of personal experiences, ask questions and remind each other that we are not alone. There are hundreds, even thousands of us that go through this experience, and each one of us can still maintain that common thread of humanity. I see “PhD Tales from the Couch” as a portal where people involved in science and PhD studies can go for advice, guidance, and support – from their peers.

.

Stay tuned for tomorrow’s launch of PhD Tales from the Couch!

.

Yevgeniy grew up in New York, but decided to transplant himself to the West Coast for his PhD studies at the Scripps Research Institute, where he studied mechanisms of gene regulation in the immune system. Recently, Yevgeniy again found himself in New York City, pursuing a post-doctoral research project in oncology. In his spare time Yevgeniy works as a Krav Maga self-defense instructor, and as a scientific writer to share his passion for fostering communication between the scientific community and the public.

.

]]>